KENT The Garden of England Day Two Part One: Canterbury

About my process. When I start out to write a blog post I often have a general idea of what I intend to cover. However, as I start writing I follow various threads. Sometimes what I intend as one post becomes more than one as I travel down various gopher holes. These travelogues are not meant to be comprehensive. They are meant to inspire and point out things or stories that are easily missed. One thing I really appreciated about our guide, Ben Sims, is that he kept telling stories that would get picked up later in our journey. If you are visiting Canterbury you can take a journey on a boat called a punt, pictured below.

HISTORIC CANTERBURY

Canterbury is a very ancient place. Human occupation began here about 10,000 years ago. Some six miles southwest of the Canterbury Cathedral is Julliberrie’s Grave, also known as the Giant’s Grave. Located near the village of Chilham [This village will be visited later] , it is an unchambered long barrow probably dated to to 3,000-4,000 BCE. The Cantiaci, a Celtic Tribe, had their main settlement at Canterbury. These Iron age settlements were here long before the Romans arrived in 43 CE. The Romans called Canterbury, Durovernum Cantiacorum or the stronghold among alders [a tree]. By 300 CE there was a Roman Amphitheatre and Temple and many buildings with red tile roofs. Once abandoned by the Romans about 410 CE it fell mainly to ruin. The Vikings, the Angles and the Saxons followed. Durovernum Cantiacorum became known at Cantwarbyring, or the township of the men of Kent.

In 561 Æthelbert became King of Kent, where he ruled for 56 years. It appears that Cantwarbyring was his capital. Although Æthelbert was a pagan he married Bertha, a Christian. Bertha and St Augustine are credited with her husband’s conversion to Christianity. St Augustine arrived in Kent on a mission to convert the pagan Anglo-Saxons to Christianity and a hundred years later much of England was Christian. Æthelbert gave land to St Augustine for a Cathedral and Abbey. The Saxon Cathedral founded in 598 CE by St Augustine, burned down in 1067. St Augustine’s was rebuilt by the Normans before becoming a Tudor royal palace and later a poorhouse, a jail and a school. When the Normans arrived they brought their own people. Lanfranc was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. He presided over the building of a new monastery and Cathedral.

As mentioned the second day I was up early and out finding CUSHMAN related places but also anything else that caught my eye. Canterbury has substantial vestiges of its walled city and its core has many Medieval buildings intact. Although very different than York it did remind me of it in some ways. York and Chester having the most substantial intact walls of English walled cities. I have already shared the CUSHMAN places but here are some others from my early morning ramble.

Let’s start with the crooked house at 28 Palace Street which dates back to 1617. It is a 3 story timber frame now reinforced with steel and once the abode of immigrant weavers. The Chimney collapsed in 1988 and the brick fell into the basement. It now houses “The Catching Lives Charity Bookshop” and I would have very much enjoyed going inside but luckily it was closed. As I only had a carry-on and had already visited another charity bookshop in town! The inscription above the door reads:

“…a very old house bulging out over the road…leaning forward trying to see who was passing on the narrow pavement below…” Charles DICKENS

Next up, 8 Palace Street is one of the most photographed buildings in Canterbury, but I did not know that at the time. Built around 1250 as the priest’s house for nearby St Alphege church which was the marriage location of Robert CUSHMAN, nearby. The timber framing and first floor overhang were added in the late 15th century, and then major extensions in 1665. It has delightful carved corbels. Definitely a building with character.

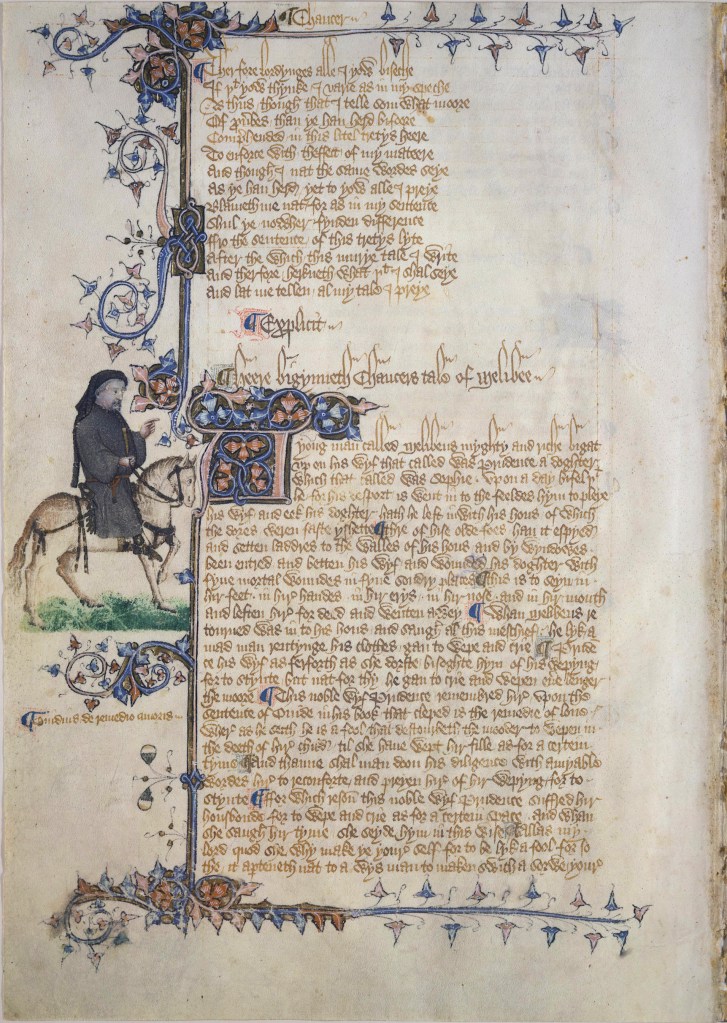

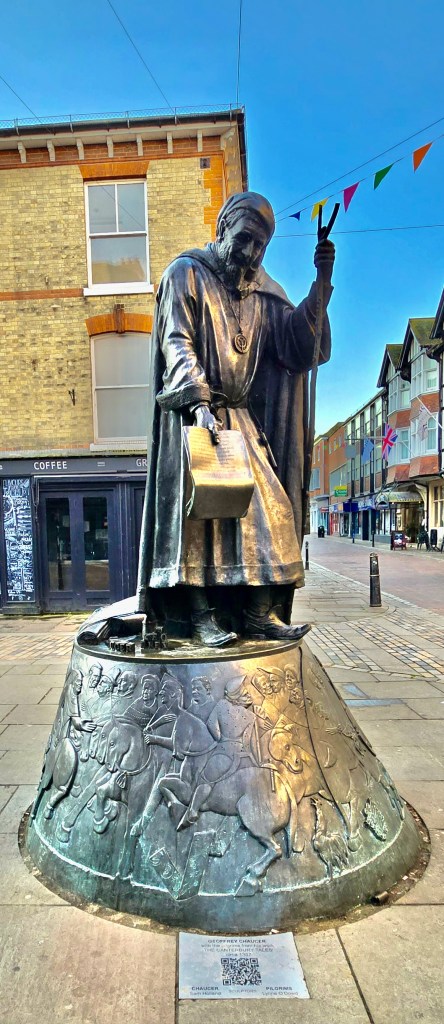

This statue of Geoffrey CHAUCER was placed in 2016. The work of sculptor Sam Holland of Kent, and the large plinth, sculpted in bas-relief, by Lynn O’Dowd of Yorkshire. Geoffrey CHAUCER wrote The Canterbury Tales. They are a collection of 24 short stories written in verse, between about 1387 and 1400. Together they make up a fictional story about a contest held by a group of pilgrims traveling from London to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas BECKET at Canterbury Cathedral. The Pilgrims Way, from Southwark Cathedral in London to Canterbury Cathedral is 90 miles and is called also called the BECKET Way. [The West direction of the Pilgrim’s way leads to Winchester in Hampshire.] Directly across the street from the statue is the early 19c Italianate building.

Just next door to the above, at 25 High Street is the Eastbridge Hospital of Saint Thomas the Martyr. Founded in the 1180’s for poor pilgrims visiting the shrine of Saint Thomas BECKET. It was restored 1832-1927. Twelve pilgrims were accommodated each night and were charged 4d for board and lodgings. In the 14c a chapel was added, and after the Dissolution the building was turned into almshouses for the poor. A few more local sites before we dive further into Saint Thomas BECKET.

Queen Elizabeth’s Guest Chambers at 43-45 High Street was established as a building site by 1200. From the 15th to 18th centuries it was know as the Crown Inn (top left). The current facade was added in the 17th century to the building of 1573. The war Memorial stands adjacent the Christ Church Gate entrance to CanteburyCathedral but was being renovated during our visit. The Sun Hotel was built in 1603 (right) and is believed by some to be a place of Charles Dickens acquaintance.

The Thomas Becket pub (lower right) dates to about 1775 when it was registered as a Trade Club for bricklayers and was known as the “Bricklayer’s Arms.” The building(s) that predates it was likely a wayfaring stop for pilgrims on there way to St. Thomas BECKET’s shrine. The last image is of the Royal Museum and Gallery designed in a Tudor Revival style by A.H. CAMPBELL and opened in 1899. It was initially named the Beaney Institute.

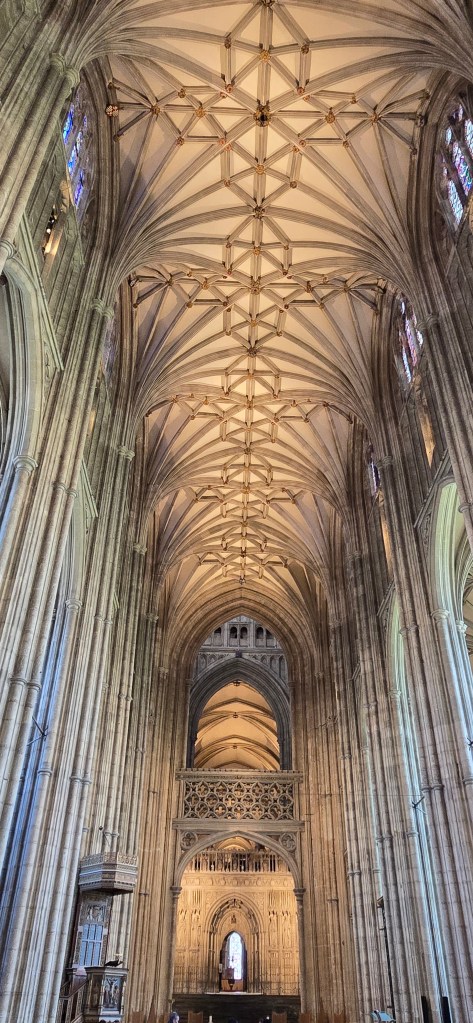

Before heading inside the Canterbury Cathedral here are a smattering of outside views. As with many historic buildings in England many are always undergoing restoration/renovation.

SAINT THOMAS BECKET

As you have seen in some of the photos above Thomas BECKET is an important name in the history of Canterbury. Becket was born the 21st of December 1019 or 1020, on the feast day of St Thomas the Apostle, at Cheapside, London, of Norman parents. Fortuitously, Thomas BECKET served in the household of Theobald of Bec, the Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1154, Theobald named BECKET Archdeacon of Canterbury. Theobald later recommended him to King Henry II for the vacant post of Lord Chancellor, to which he was appointed in January 1155. Beckett and King Henry II became friends. Becket was nominated as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162, after the death of his mentor, Theobald.

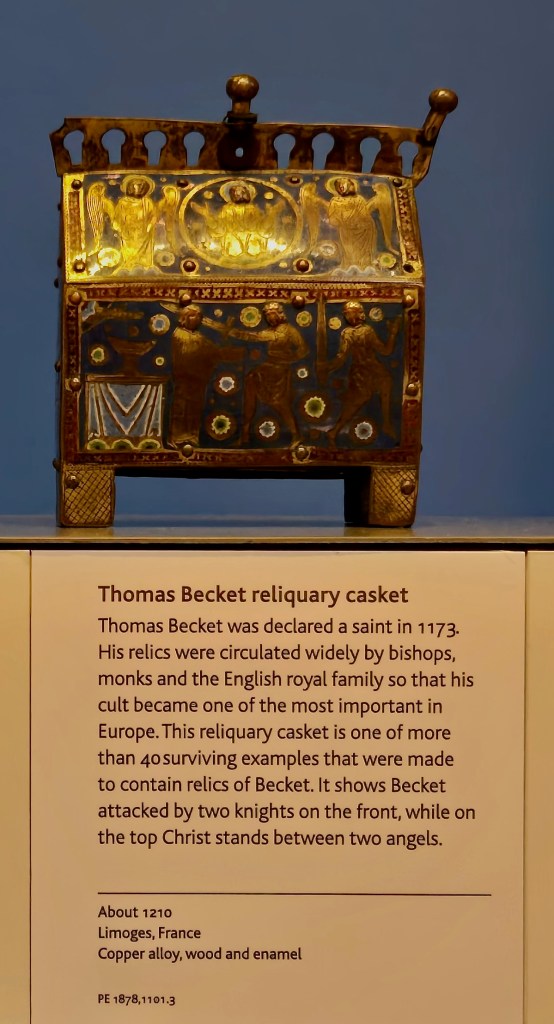

I had seen the film Becket (1964) with Richard Burton as Thomas BECKET and Peter O’Toole as King Henry II, but I only vaguely remembered the story. While at the British Museum one of the few things, outside my main focus, that I photographed was this reliquary casket. At least 45 reliquary caskets survive depicting the story of Thomas BECKET. Many are thought to have been made in Limoges, France. I would continue to meet Thomas Becket in many places.

During my rambles I picked up 4 slim books at the Oxfam charity used bookshop on High Street in Canterbury. Among them was a book called Becket’s Murderers by Nicholas Vincent. I quote from the opening:

“As David Knowles long ago pointed out, there is no single event in the history of the Middle Ages of which we know more than the murder of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, on 29 December 1170”

At one time King Henry II and BECKET were friends, but upon BECKET’s ascension to Archbishop of Canterbury, the struggles between the power of the church and that of the king began to fray that friendship. BECKET was excommunicated for 7 years but finally returned in a compromise with Kind Henry II in 1170. BECKET then excommunicated 3 churchmen, including the Archbishop of York. He was upset that he had crowned Henry’s eldest son as joint king , which should have been BECKET’s role. This upset King Henry II who wanted the Archbishop reinstated. The monk Edward GRIM writing in 1180 states that King Henry II was at his castle at Bures, Normandy, Christmas 1170 when he said referring to Thomas BECKET:

“What miserable drones and traitors have I nourished and promoted in my household, who let their lord be treated with such shameful contempt by a low-born clerk!”

This is oft quoted later as “Will no one rid me of this troublesome priest?” Reportedly, 4 knights—Reginald Fitzurse, Hugh de Morville, William de Tracy and Richard le Breton—traveled from Normandy to Canterbury with the intention of forcing BECKET to withdraw his excommunication of the Archbishop, or take him back to Normandy. The day after their arrival, they confronted BECKET in Canterbury Cathedral Tuesday 29 December 1170. BECKET resisted and the 4 ended up killing him. None, at the time, believed that Henry II wanted him to be killed. However, his words ultimately had that effect. Hundreds of clerics including archbishops were murdered with some regularity throughout the realm in this time frame. What is different about BECKET is that he became incredibly famous. In the book by Ian Mortimer, “Medieval Horizons: Why the Middle Ages Matter” tells us that pilgrims to BECKET’s tomb brought in Ł400 per year. The altar of the Sword’s Point is near the spot where Thomas BECKET was murdered lies in the Martyrdom Chapel. There was a small altar that had a reliquary containing the point of the sword which had cut into his head. Pilgrims came to kiss the flagstones, said to bear the marks of his final footprints.

In July 1174 King Henry II walked from London to Canterbury barefoot. He prostrated himself before Becket’s shrine, and was whipped by the monk’s of the priory. He spent the night in prayer and penitence by the tomb of his former friend Thomas BECKET. Between BECKET’s death in 1170 and his removal to the shrine in the Trinity Chapel in 1220, his body lay in a marble tomb in the crypt. Even after the move, the empty tomb continued to be venerated as a site which had held the saint’s body. The Corona Chapel, held a golden head reliquary, containing a piece of Saint Thomas’s skull In 1314 it was remade with gold and jewels. The shrine was not installed in the Corona until 1220, in a ceremony at which the King Henry III was present. The Corona Chapel can be seen beyond the Quire and the Trinity chapel at the far east of the cathedral. BECKET’s shrine became a major pilgrimage site, attracting visitors from across Europe.

The Trinity Chapel became the location of Thomas BECKET’s remains in a lavish tomb. King Henry VIII during the Reformation in 1538 ordered the destruction of the BECKET Shrine, and his bones were either burned or reburied elsewhere. No one knows there location. A single candle marks the spot where the shrine used to stand.

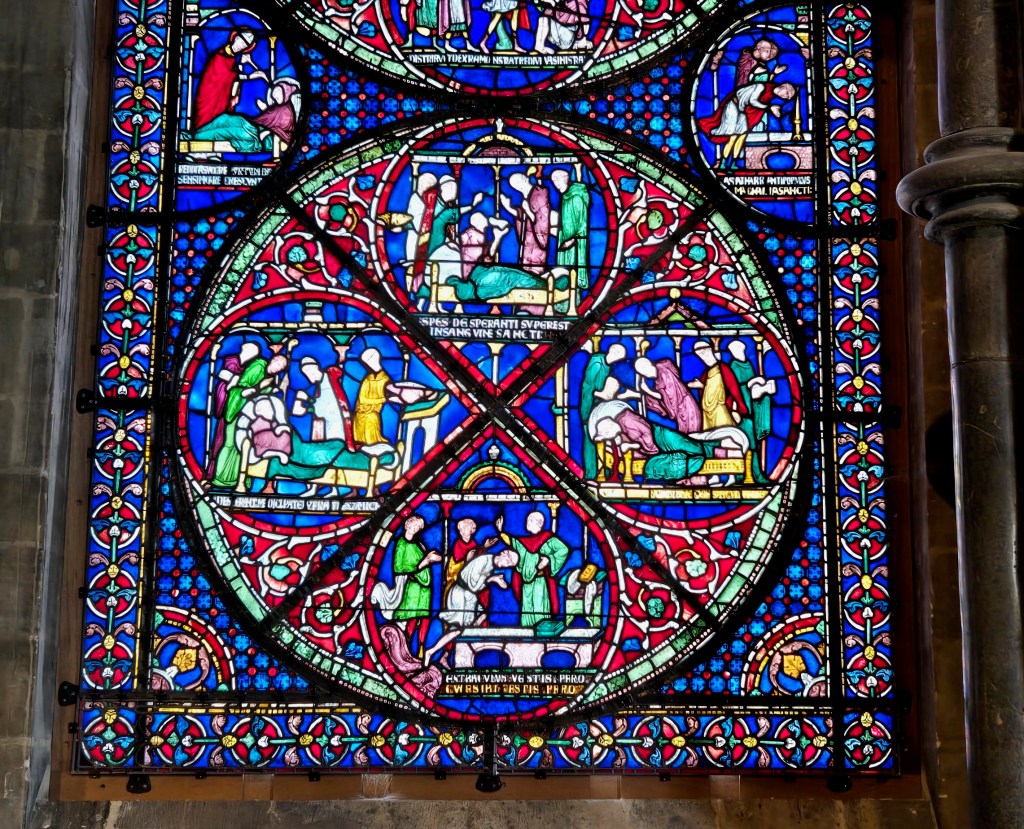

Surrounding the Trinity Chapel are the Miracle windows that depict miracles ascribed to Saint Thomas BECKET. The oldest date back to the 12th century and were installed to surround Becket’s shrine in the Trinity Chapel. After a fire destroyed much of the cathedral in 1174. Some glass panels have been restored or replaced, but much of the original early 13th century glass remains.

Thomas Becket was canonized as a saint in 1173 by Pope Alexander III just three years after his assassination.

Adjacent the Trinity Chapel is the effigy of Edward Plantagenet (1330-1376), The Black Prince. He was the son of King Edward III and was his eldest son, but he died before his father. He was of an age where nobility was expected to fight and he was a fearsome warrior. Edward’s son became King Richard II after King Edward III’s death. King Richard was succeeded, by his son, King Henry IV whose effigy along with his wife Joan of Navarre are below.

Before we leave Canterbury for Leeds Castle a bit more of the Cathedral and grounds. Yes, the architecture is awe inspiring, but even more so is the fact that these structures were built back in the medieval period which we tend to view condescendingly. If you look closely you will see the candle of Thomas BECKET behind King Henry IV (1367-1413) and with his wife Joan of Navarre.

And finally I leave you with these steps, worn down over time by the millions of pilgrims and visitors to Canterbury cathedral. If you go, do sign up for a guided tour, it will give you much greater appreciation for the history and treasures here.

Kelly Wheaton ©2025 – All Rights Reserved